Appeals court probes limits of Trump's broad immunity claim in 2020 election case

Washington — A federal appeals court questioned the limits of a broad claim of presidential immunity put forward by former President Donald Trump, peppering his attorney with extreme hypothetical scenarios during contentious oral arguments on Tuesday.

Trump's attorney argued that presidents are immune from criminal prosecution for actions taken in office, unless they are first impeached by the House and convicted by the Senate. The three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit asked whether that argument would apply if the president took a range of clearly illegal actions, including ordering the assassination of a political rival or selling pardons.

"You're saying a president could sell pardons, could sell military secrets, could order SEAL Team 6 to assassinate a political rival," Judge Florence Pan said during one exchange, referring to the elite Navy unit. John Sauer, the attorney representing Trump, argued that impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate would be required before a criminal prosecution.

James Pearce, a member of special counsel Jack Smith's team, warned the court that accepting Sauer's view of criminal liability for a former president following impeachment and conviction by the two chambers of Congress is "wrong for textual, structural, historical reasons, and a host of practical ones."

"It would mean that if a former president engages in assassination, selling pardons, these kinds of things and then isn't impeached and convicted, there is no accountability for that individual," he said.

A lower court has already ruled that Trump is not absolutely immune from prosecution, and the outcome of the appeal could potentially derail the charges brought by Smith over Trump's actions surrounding the 2020 presidential election. Trump faces four charges in the case and has pleaded not guilty.

If the D.C. Circuit rules against Trump and allows the prosecution to proceed, Sauer requested the court put its decision on hold to allow the former president to appeal to either the full D.C. Circuit or Supreme Court.

Trump made brief remarks to reporters following the arguments, arguing he did "nothing wrong" and was "working for the country." The former president said his actions involved investigating claims of voter fraud in the 2020 election, though there was no evidence of widespread fraud that would've changed the outcome of the electoral contest. Prosecutors have alleged Trump was engaging in illegal acts to remain in power despite losing at the ballot box.

Trump claimed there would be "bedlam" in the country if his presidential bid is damaged as a result of the charges brought against him. Asked if he would tell his supporters to refrain from violence, Trump did not answer as he walked away from reporters.

The oral arguments

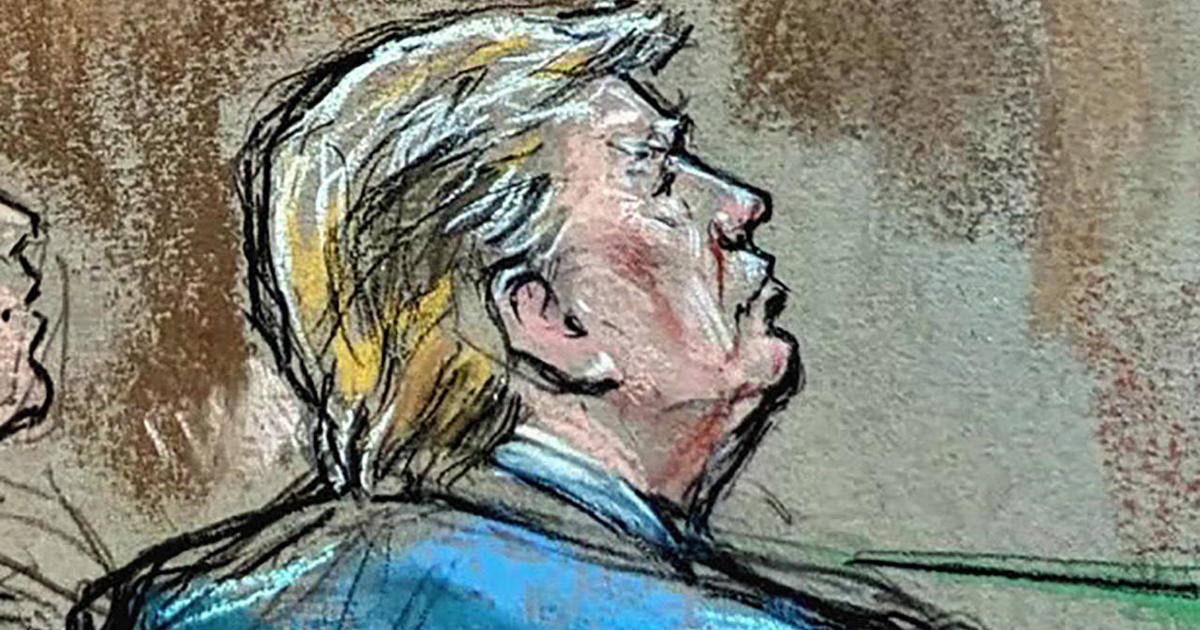

Trump and Smith both attended the arguments, the first time they appeared in court together since Trump's arraignment in the case in August. The former president, wearing a suit and red tie, entered the small but crowded courtroom looking very serious, and Smith watched him as he entered. The whole room, which had been quite talkative, went completely silent and the atmosphere became palpably tense. Trump took his seat next to his lawyers and leaned in to confer with them before the arguments began.

Judges Karen LeCraft Henderson and Michelle Childs are the other two members of the panel hearing Trump's appeal. From the outset, the three judges appeared skeptical that he is entitled to the sweeping immunity from criminal prosecution that Trump claims to have.

"I think it's paradoxical to say that his constitutional duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed allows him to violate criminal law," Henderson, appointed by President George H.W. Bush, told Sauer.

As arguments got underway, Childs immediately questioned Sauer about whether the D.C. Circuit has jurisdiction to hear Trump's appeal at this time — an issue raised in a friend-of-the-court brief in late December, and which the panel told lawyers for Trump and the government to be prepared to discuss.

"We don't have an explicit communication here with respect to anything in the Constitution or statute," Childs told Sauer.

Turning to the merits of the case, Sauer told the judges that allowing the criminal prosecution of a former president over actions taken while in office would "open Pandora's Box from which this nation may never recover."

He questioned whether past presidents, such as President George W. Bush and Barack Obama, could face criminal charges stemming from official actions during their presidencies.

Pan, named to the bench by President Biden, posed a series of tough questions to Sauer, including on how the court should balance the importance of presidential immunity with the public's interests. She told Sauer that his argument advanced the need for the executive to be able to act without hesitation or fear, and make decisions without the fear of prosecution.

But Pan raised other executive branch interests that she said are "countervailing," such as the transfer of presidential power under the Constitution and the enforcement of criminal laws by the Justice Department.

"It seems to me if we're weighing executive interests versus public interests — public interest in things like the integrity of an election — that President Trump's position is not fully aligned with the institutional interests of the executive branch," she said. "And in this balancing test, that weakens the executive power that he is trying to assert."

Trump has claimed that his prosecution by Smith is politically motivated, an allegation Sauer raised before the D.C. Circuit.

After Childs said a prosecutor is "impartial" and does not make political judgments when pursuing charges, Sauer replied, "I think that has no basis in the context of the current prosecution, where the current incumbent of the presidency is prosecuting his number one political opponent and his greatest electoral threat." (Mr. Biden and the White House have stressed the independence of the Justice Department, and there is no evidence that the president has been involved in pursuing or influencing Trump's prosecution.)

Pearce, appearing for the Justice Department, later told the judges that the decision to prosecute Trump reflects the "fundamentally unprecedented nature" of the criminal charges.

"Never before has there been allegations that a sitting president has, with private individuals and using the levers of power, sought to fundamentally subvert the democratic republic and the electoral system," he said. "And frankly, if that kind of fact pattern arises again, I think it would be awfully scary if there weren't some sort of mechanism by which to reach that criminally."

Trump's expression remained serious over the course of the arguments. He watched Sauer intently as the judges questioned him. Smith mostly stared straight ahead, with no noticeable interaction between the two men. As Trump left the room at the end of the proceedings, he turned around and surveyed the room in Smith's direction, but the special counsel had his back turned.

Trump's immunity claim

In written briefs filed ahead of Tuesday's hearing, the former president's legal team wrote the charges are "unlawful and unconstitutional" because they target "official acts" Trump took as president. Trump's attorneys argued that because the alleged conduct described in Smith's indictment occurred while Trump was in office, the Constitution prescribes that he can only be criminally prosecuted if first convicted by the Senate following an impeachment trial.

"Before any single prosecutor can ask a court to sit in judgment of the President's conduct, Congress must have approved of it by impeaching and convicting the President. That did not happen here, and so President Trump has absolute immunity," Trump's attorneys wrote, pointing to the 2021 impeachment of the former president by the House, after which he was acquitted by the Senate.

The special counsel, however, rebutted those claims outright in a filing of his own. He warned that Trump's legal theory "threatens to license Presidents to commit crimes to remain in office."

Prosecutors argued that even if Trump had some level of immunity for official acts carried out in his role as president, "the indictment contains substantial allegations of a plot to overturn the election results that fall well outside the outer perimeter of official Presidential responsibilities." Smith's team also argued that Trump was charged with different crimes than those he faced during his impeachment trial, so no limitations tied to past congressional proceedings should be placed on his criminal trial.

The House impeached Trump on a single article charging him with "incitement of insurrection." He faces four different counts for his alleged conduct surrounding the 2020 election, including obstruction of an official proceeding and conspiracy to defraud the United States.

Tuesday's arguments came after U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan denied Trump's initial attempt to dismiss the case on grounds of presidential immunity. The judge found that the presidency "does not confer a lifelong 'get-out-of-jail-free' pass," and said Trump may be subject to "federal investigation, indictment, prosecution, conviction and punishment for any criminal acts undertaken while in office."

Chutkan has set Trump's criminal trial for March 4, but the case is currently on hold as the immunity question is considered by higher courts.

In an attempt to expedite the proceedings, Smith's team asked the Supreme Court to grant an unusual request to take up the case before the appeals court considered it. But in an unsigned order, the high court last month opted not to take up the landmark case ahead of schedule. The decision does not preclude the losing party — either Trump or Smith — from seeking the Supreme Court's review again once the D.C. Circuit has ruled.

The jurisdiction question

In a friend-of-the-court brief filed Dec. 29, American Oversight, a liberal watchdog group, argued that Trump could not ask the appeals court to review Chutkan's order denying presidential immunity. The group urged the D.C. Circuit to dismiss the appeal and send the case back to the district court for trial "without further delay."

Citing a unanimous 1989 Supreme Court decision authored by Justice Antonin Scalia, the group said an order denying immunity in a criminal case can only be appealed when the immunity claim "rests upon an explicit statutory or constitutional guarantee that trial will not occur." The high court has identified only two constitutional guarantees against trial that meet this standard, American Oversight argued: the double jeopardy clause and speech or debate clause, which shields members of Congress from being questioned about their legislative actions.

"Mr. Trump asserts immunity under structural constitutional principles and an unstated negative implication of the Impeachment Judgment Clause. Neither claim rests upon any explicit textual guarantee against trial," lawyers for the group told the D.C. Circuit in their filing.

Trump, they said, could return to the D.C. Circuit and press his presidential immunity claim after conviction, if he is found guilty on any of the four charges he faces.

In an unsigned order last week, the judges instructed lawyers for both sides to be prepared to address during oral arguments "any inquiries by the court regarding discrete issues raised" in friend-of-the-court briefs.

Both Sauer and Pearce argued that the court did, in fact, have jurisdiction to take on the case, with the former president's attorney contending that waiting until after trial would only further jeopardize Trump's legal standing. Pearce agreed that the judges had the legal authority to take on the question of immunity now instead of waiting until after trial.

"Doing justice is getting the law right," Pearce said, indicating the special counsel would rather delay the March trial to ensure the question is fully decided.

Sauer argued that if the prosecution was allowed to proceed, it would be "tailor-made for cycles of recrimination" and other presidents could face similar threats down the line.

It's unclear how quickly the D.C. Circuit will issue a decision on the immunity matter, though it has acted swiftly in setting deadlines for filings and holding arguments. If the appeals court issues a decision on whether Trump is immune from federal prosecution, it can be appealed to the Supreme Court.

for more features.