Neurosurgeon works to slow Alzheimer's progression, treat addiction with cutting-edge technology

Anyone who has had experience with Alzheimer's disease knows the agony of watching someone fade away as it steals memory and at the end – a person's own identity. Tonight – we'll show you an experimental way to try and beat back Alzheimer's. It's been tested on just a handful of patients – but it caught our attention because of the doctor involved, Dr. Ali Rezai, who 60 Minutes first met 20 years ago. Dr. Rezai is a neuroscience pioneer who has developed treatments for Parkinson's disease and other brain disorders. Over the last year we followed this master of the mind as he attempted to delay the progression of Alzheimer's disease and its worst symptoms using ultrasound. We saw a cutting-edge approach to brain surgery…with no cutting.

Dr. Ali Rezai: If we can, we should not be doing brain surgery.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You're a brain surgeon!

Dr. Ali Rezai: I am, but I should be out of a job, because brain surgery, it's cutting the skin, opening the skull. It can be barbaric.

It looked like a scene from a sci-fi movie. A halo wrapped patient, pushed into a tube…as a team of doctors manipulate his brain from the other side of the glass.

Dr. Ali Rezai allowed us to witness his revolutionary attempt to use ultrasound to slow down the cognitive decline in three patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. It's never been done before.

Dr. Ali Rezai: There's no miracle cures here. It's advancing medicine with calculated risks and pushing the frontiers.

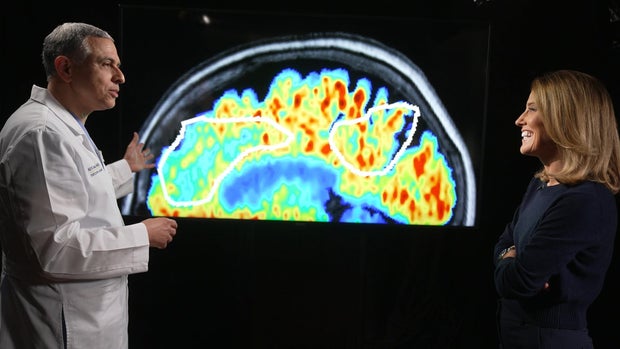

Dr. Rezai and his team are focused on these red patches in the patient's brain scans. The red indicates the densest beta-amyloid protein. That gummy protein is believed to play a major role in Alzheimer's by disrupting communication between brain cells.

Dr. Ali Rezai: In people with Alzheimer's it accumulates much faster. And over time, these protein aggregates, we call them plaques. Like plaques in the arteries, they keep on accumulating and impacting function.

There are two FDA approved drugs on the market …that can help break up that brain plaque. Aducanumab was approved in 2021…followed by lecanemab last year. Both are given intravenously… but they work slowly.

Dr. Ali Rezai: Typically, you go into the clinic, and you get an IV, and you have the antibody infusion over one to two hours. And you have to do it once a month or twice a month for 18 months and longer. And during those 12 to 18 months, the brain is continuing to progress. Alzheimer's is not going away.

It takes so long because the drugs have a hard time getting through something called the blood brain barrier. This tight filter of cells line the blood vessels to keep toxins from leaking into the brain…but it also prevents almost all of the medication from getting in too.

Dr. Rezai thought he could solve that problem with ultrasound - the same technology that's been used for 70 years to give doctors a view of organs and fetal development.

He chose ultrasound because it easily penetrates the skull and can be focused -- like sunlight through a magnifying glass - to help open the blood brain barrier and allow the drugs to rush in.

Dr. Ali Rezai: This way we're getting the payload-- the therapeutic payload exactly to the area it needs to go with a high penetration. But we gotta be careful because we wanna be safe about this. You don't wanna deliver too much. Don't wanna open the blood-brain barrier too much…

Sharyn Alfonsi: Because if you open it too much, what could happen--

Dr. Ali Rezai: You can get bleeding in the brain, you can get swelling in the brain, you can get many other problems. So you have to get it just right.

We will show you exactly how that worked and the early results in a minute…

But to understand why one of the country's most accomplished brain surgeons is betting on ultrasound…

You have to go back to 2002…when Dr. Rezai first caught our attention in a story Morley Safer reported on treating Parkinson's disease.

Dr. Rezai in 2002 Morley Safer piece: "Look up…show me your teeth...stick your tongue out…Very good."

Dr. Rezai was among the first to implant a pacemaker-type device in the brain which stopped uncontrollable movements suffered by Parkinson's patients.

Dr. Rezai in 2002 Morley Safer piece: "It's like traveling through a labyrinth as in the Greek myth and around every corner you have that bloodthirsty monster that can jump on you so you want to be careful to avoid these areas."

That kind of implant surgery is now routine for advanced Parkinson's. Dr. Rezai went on to write hundreds of scientific papers, secure dozens of patents and present his Parkinson's research to Congress and the White House. He could have gone to any big city research center, but, true to form, he chose to try something different and moved to Morgantown, West Virginia – where he is the executive director of the Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute.

Dr. Ali Rezai: It was a fantastic move, because we're able to achieve so many things that would have been difficult at other institutions. Sometimes in the bigger institutions you may not be hungry as much for it, or you may have a thousand different agendas and priorities. Here we think we have a very nimble and agile team that can quickly get outcomes.

Like in 2019…this is video Dr. Rezai's team took when they were among the first to use ultrasound to treat tremors. For 15 years, Dan Wahl had been suffering from essential tremor- a neurological disorder.

(2019 RNI video)

Dr. Ali Rezai: You OK?

Dan Wahl: I'm OK.

Dr. Ali Rezai: You got a hat on now. Alright very good.

Rezai's team focused ultrasound into a part of the brain called the thalamus to destroy a pin-point sized patch of tissue doctors believed was responsible for the tremors.

Dr. Ali Rezai: These are the 980 elements converging right there.

Wahl was awake during the procedure.

Doctor: Touch my finger with your finger…

After two hours, the 71 year old's tremor was gone.

Dan Wahl: I'm still afraid I'm gonna drop it.

Doctor: You got it!

Dan Wahl: I got it.

Doctor: Really good. Do you wanna show off?

Mrs. Wahl: Praise the lord.

That success helped convince Dr. Rezai that focused ultrasound could be adapted to patients with other brain disorders…including Alzheimer's disease.

Dan Miller: My first symptoms that I noticed were that I was having trouble typing at work.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Did you think you had Alzheimer's?

Dan Miller: No. I didn't

Dan Miller is just 61 years old. His wife Kathy began noticing changes four years ago.

Kathy Miller: He kinda hid it pretty well. And then I noticed he was-- having trouble-- his clothes would be backwards and those kinds of things.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Just little things.

Kathy Miller: Just little things. Yes.

A scan of his brain…revealed what Dan had been hiding. The red spots indicated a build up of those beta-amyloid proteins…the so-called brain plaque…a marker of Alzheimer's. Dr. Rezai explained to Miller he couldn't cure him of the disease, but he hoped to slow its progression.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Why take part in the trial if it's not a cure?

Dan Miller: I have to explain to you that I was at the point, you know, like in Dante's "Inferno" where-- where it says, "Abandon all hope, (laugh) you who enter here." For me it was just-- you know, let's do this. You know? What do I have to lose?

Here's how it worked. Hours before the procedure, Miller was given an IV treatment of aducanumab, one of those two new drugs to reduce beta-amyloid plaque.

Miller was then fitted with this million dollar helmet…similar to the one the team used to treat tremor patients. it directs nearly a thousand beams of ultrasound energy at a target the size of a pencil point.

Dr. Ali Rezai: Basically a patient lies on the MRI table and the head goes inside the helmet and the patient is immobilized with a halo or with a mouthpiece because we don't want movements to cause errors in our targeting in the brain.

Once inside, the MRI machine gave Dr. Rezai a 3D-view of the plaque he would target in Dan Miller's brain. The next step was an IV solution that contained microscopic bubbles. When hit with ultrasound energy, the bubbles pry open that blood brain barrier.

Dr. Ali Rezai: The bubbles start vibrating.

Sharyn Alfonsi: They're moving.

Dr. Ali Rezai: They're moving. They start expanding so you can open the barrier temporarily. Now it's open for 24 to 48 hours and then it reseals. So this gives you a tremendous opportunity for 24 to 48 hours with the barrier being open so now therapeutics can get inside the brain.

You can't hear ultrasound…that noise is a signal to tell Rezai's team the ultrasound is doing its work.

Dr. Ali Rezai: Each dot represents an area where all the waves-- all the ultrasound waves converge and open the blood-brain barrier.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So this is just one blast, if you will?

Dr. Ali Rezai: One blast getting there.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And you're hitting one point?

Dr. Ali Rezai: One point, and then it moves to the next one.

Even though patients were awake, they told us they didn't feel a thing. It all took a couple of hours and they went home when it was over. The three patients were given the treatments of ultrasound with infusion once a month over six months. The result: beta-amyloid plaque targeted with ultrasound were reduced 50% more than areas treated by infusion alone. Dr. Rezai shared the three patients' brain scans with us.

Dr. Ali Rezai: And the red indicates more density of beta amyloid plaques in the brain so you can see as you treat it with ultrasound…

Look closely at the areas outlined in white that were targeted with ultrasound and the drug.

Dr. Ali Rezai: You get reduction.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Whoa.

Dr. Ali Rezai: Right there--

Sharyn Alfonsi: That's after?

Dr. Ali Rezai: That's after. You can see the plaques are very significantly reduced by opening the blood-brain barrier just in one -- area.

Dan Miller and the third patient in the trial had larger areas of their brain targeted with ultrasound.

Dr. Ali Rezai: And this is his baseline and then you can see here after--

Sharyn Alfonsi: Wow.

Dr. Ali Rezai: --26 weeks, there's a very dramatic reduction in the beta amyloid in the areas as outlined by this white mark.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And now we're gonna look at patient number three.

Dr. Ali Rezai: And this patient underwent antibody infusion therapy plus ultrasound. You can see this area--

Sharyn Alfonsi: Wow.

Dr. Ali Rezai: --which is really amazing. The ultrasound opened the blood-brain barrier and the antibody went in faster and cleaned out the plaques.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What was your reaction when you saw this scan?

Dr. Ali Rezai: Uh. I mean, my jaw dropped. I'm like, "Whoa." I-- I was actually even in the clinic seeing patients and the PET scan technician called and said-- "Oh yeah, there's a big change." I'm like, "How do you know? We have to analyze it." He was like, "No, you can see it on the screen." So…

Sharyn Alfonsi: What did you think when Dr. Rezai shared the scans with you?

Dan Miller: It was surreal.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You can really see it. You don't have to be a doctor to understand what's going on there.

Kathy Miller: No. Absolutely not.

Kathy Miller says she can see it in her husband, too…who slips up once in a while…but hasn't slipped further away.

Kathy Miller: He has trouble finding things. I'll send him into the kitchen to get somethin' and he's like, "It's not there." And like, "Yes, it is. I can see it." But he can't see it. But if that's the worst, that's nothing.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You'll take it.

Kathy Miller: I'll take it.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You feel hopeful about the future?

Dan Miller: I do. Yes. I learned that what I needed to do is accept that the old Dan is gone and then-- start working on the new me, which has a future.

Dr. Rezai's team told us there has been no change in the ability of the three patients to do their daily activities since the ultrasound treatments ended in July.

Now that Dr. Rezai has shown focused ultrasound can clear beta-amyloid plaques faster, he has FDA approval to use ultrasound to try and restore brain cell function lost to Alzheimer's.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What's the result of breaking up all those plaques to the damage that's already been done to the brain?

Dr. Ali Rezai: We don't know if it's gonna reverse the damage to the brain, because Alzheimer's, the underlying cause is still occurring. So we have another study that we're looking at with ultrasound. First, clear the plaques. Then deliver ultrasound in a different dose to see now if we can reverse it or boost the brain more for people with Alzheimer's.

The human brain contains 100 billion neurons. That's as many cells as there are stars across the milky way. Dr. Ali Rezai has spent 25 years exploring this frontier of medicine. The surgical techniques and therapies he pioneered are in use around the world. Dr. Rezai allowed us to see his latest research over the last year at the Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute in Morgantown, West Virginia. It includes revolutionary treatments for a brain disease suffered by 24 million Americans - addiction. The results so far have been life changing for the people we met once trapped by drugs.

Gerod Buckhalter: Looking back, I didn't have a chance.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What do you mean you didn't have a chance?

Gerod Buckhalter: I couldn't do anything without having that drug--um in my system.

Gerod Buckhalter is the son of a coal miner. At 6 foot 3, he was a high school football standout…who dreamed of playing wide receiver at Penn State…but after a shoulder injury, he got hooked on painkillers.

Gerod Buckhalter: The very first time that I-- that I took that first pill, um -- I-- I knew that I wanted that feeling for the rest of my life.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What did it feel like?

Gerod Buckhalter: It's just pure euphoria.

He took us to where he said he often went to buy drugs, including heroin.

Gerod Buckhalter: Everybody in Morgantown knows to come here. I was probably 17, 18 years old…you know...just a kid.

Buckhalter still looks like an athlete…it's hard to imagine he was an addict for more than 15 years. He told us he does not remember how many times he overdosed and that he couldn't stay clean for more than four days at a time.

Gerod Buckhalter: I didn't know where I was gonna sleep some nights. You know, my family didn't want me around anymore. I just-- I did so many things to hurt them that, you know, it was just too much for them to deal with.

Four years ago, a psychologist who'd worked with Buckhalter introduced him to Dr. Ali Rezai, who was gearing up to perform a new kind of brain surgery to treat severe addiction.

Dr. Ali Rezai: Our protocol was people that have failed everything.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Once you've tried everything.

Dr. Ali Rezai: Everything. Residential programs, multiple failures, detox multiple times, outpatient, inpatient, multiple overdoses.

Gerod Buckhalter: I think he classified it as-- end-stage drug user.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I mean, end stage makes you think that this is the end of your life.

Gerod Buckhalter: Correct. And hearing that at the age of 34 um, it - it was crazy.

Dr. Rezai thought he might be able to adapt technology he helped develop years earlier to treat Parkinson's disease to treat people with severe addiction.

Dr. Ali Rezai: We've been able to map out with neuroscience imaging there's a specific part of the brain that is electrically and chemically malfunctioning that is associated with addiction.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So it's not just willpower. It's what's happening in the brain.

Dr. Ali Rezai: It's a brain disease, it's an electrical and chemical abnormality in the brain that occurs over time with recurrent use of drugs. And this can be any substance, alcohol, can be opioids, amphetamines, cocaine and they all are involving the same part of the brain.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And so your idea was what with the implant?

Dr. Ali Rezai: Parkinson's we implant that in the movement part of the brain that is electrically malfunctioning causing shaking. In this case, we're going in the behavioral regulation, anxiety, and craving parts of the brain.

Dr. Rezai has seen the impact of addiction in his community. The problem is so severe in Morgantown...a vending machine dispenses the overdose antidote narcan for free.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse agreed to support Dr. Rezai's attempt to fight addiction with a brain implant. In 2019, the FDA gave him a green light to attempt the groundbreaking surgery.

That is Gerod Buckhalter. He agreed to be the first addiction patient in the U.S. to get the implant. Dr. Rezai's team interviewed him the day before the surgery.

Gerod Buckhalter (during Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute pre-surgery interview): "The best outcome possible would be just to cut the cravings out, make me feel a little bit better. If you know, if those couple of things happen you know...that's all I could possibly ask for."

Gerod Buckhalter: At that time I was so desperate for a better life that I was willing to do just about anything and I signed up to do it.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I think some people might look at this and think, "An electronic implant in the brain sounds a little creepy."

Dr. Ali Rezai: People maybe 50 years ago, they say "A implant in the heart sounds creepy." Now it's, like, normal. Twenty-five years ago, people are saying, "What are you doing? You're putting an implant in the brain for Parkinson's?" but now it's routine part of standard of care for advanced Parkinson's.

This is video from the seven-hour procedure. A surgery so new…it didn't have a name yet. Dr. Rezai opened a nickel-sized hole in burkhalter's skull. then he directed a thin wire with four electrodes deep inside.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Gerod was awake during the surgery. Why was that necessary?

Dr. Ali Rezai: To map the brain we have tiny microphones the size of a hair we put inside the brain. And they're going slowly with micro-robots. They go at increments of a thousandth of a millimeter. Very slow, we drive them into the brain, and we're listening to the neurons talking to each other. In addiction, we want to find the area in the reward center, so that confirms where we are in the brain. Once we listen, we say, "Okay, that's the right sound," then we put the final therapeutic pacemaker.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What does it sound like?

Dr. Ali Rezai: Static electricity, which may be electricity to you but its music to my ears.

Music because, Dr. Rezai says, it's a signal that he found the right spot in the brain for the implant.

Once in place, the wire was connected to a device placed below the collarbone.

The electrical pulses it sends to the brain are intended to suppress cravings. Buckhalter said it was painless. Post surgery, the system is adjusted remotely with a tablet computer as needed.

Gerod Buckhalter: When they turned the-- the unit on it was an immediate change.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What was the change?

Gerod Buckhalter: Just felt better. You know, just felt like I did prior to ever using drugs, but a little bit better. And it was at that point that I knew that I was gonna have a legitimate shot at doing well.

In all – four patients with severe drug addiction had the implant surgery. One had a minor relapse. Another dropped out of the trial completely. But two have been drug free since their operations, including Gerod Buckhalter, whose been clean for four years.

Sharyn Alfonsi: If you hadn't met Doctor Rezai, if you hadn't gone through this implant, do you think you'd be sitting here talking to me today?

Gerod Buckhalter: You may be talking to my parents you know, those that have lost their-- their loved ones to a drug overdose, but you wouldn't be talking to me. There's-- there's no doubt about that.

The surgery was a success but opening someone's skull is always risky. Dr. Rezai thought he could reach more patients quickly if he used ultrasound. He was already using it to treat other brain disorders…and was convinced focused ultrasound could target the same area of the brain as the implant.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is this brain surgery without a knife?

Dr. Ali Rezai: It is, indeed. So this is, there's no skin cutting. There's no opening the skull. So it is brain surgery without cutting the skin, indeed.

Dr. Rezai explained how his team would be the first to treat addicts by aiming hundreds of beams of ultrasound to a precise point deep inside the brain.

Dr. Ali Rezai: So the area that we're treating is the reward center in the brain, which is the nucleus accumbens, which is right down at the base of this dark area. And then we deliver-- ultrasound waves to that specific part of the brain, and we watch how acutely, on the table your cravings and your anxiety changes in response to ultrasound.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How is the ultrasound making a change here?

Dr. Ali Rezai: Ultrasound energy is changing the electrical and chemical milieu, or activity, in this structure in the brain involving addiction and cravings.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Just resetting them and giving them kind of a fresh start?

Dr. Ali Rezai: At this point, it seems like the brain is being reset, or rebooting of the brain, and the cravings are less, they are managed, anxiety is better. So now that allows them to interact with the therapist. It's very important to know that this is not a cure, but an augmentation of the therapy by reducing the cravings and anxiety that's so overwhelming that the therapist has difficulty working with the patient.

Last February, we watched Dr. Rezai use focused ultrasound to treat Dave Martin who told us he has been surrounded by friends and family who use drugs his whole life.

Sharyn Alfonsi: When did you start using drugs?

Dave Martin: When I was seven years old.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Seven?

Dave Martin: Yes. I did drugs for 37 years.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What kind of drugs were you using?

Dave Martin: Anything I could get my hands on.

Inside the MRI, Martin was shown these images of drug use to stoke his cravings.

A simultaneous brain scan allowed Dr. Rezai and his team to immediately spot the area in the nucleus accumbens that was most active.

90-watts of ultrasound energy were beamed at a target the size of a gumdrop.

Within minutes, we noticed Martin's foot - that had been anxiously bouncing - was still. And he told Rezai's team that those same images of drugs he was shown earlier, were now… not sparking the need for a fix.

Dave Martin: The day of the procedure, it was the best day of my life. I didn't experience the same effect as, like, the times before --

Sharyn Alfonsi: You didn't feel like, "I need that." I want that --

Dave Martin: No. I didn't feel like I needed the urge or the desire to use wasn't there anymore.

Dr. Ali Rezai: So within 15 to 20 minutes of treatment, the craving and anxiety melts away, and we're seeing this pattern in multiple instances.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Then they can walk away after this? There's no--

Dr. Ali Rezai: They get off the table and go home.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And how long does this entire procedure take?

Dr. Ali Rezai: One hour.

Sharyn Alfonsi: One hour.

Dr. Ali Rezai: One hour.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Have you been around people still using drugs?

Dave Martin: Yes, yes, unfortunately, I have. Um.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And what happens?

Dave Martin: It didn't even trigger me. I used to use intraven-- intravenously with needles and… It was a little while ago not too far back but this one individual was tryin' to hit theirself. And they couldn't hit. And they asked me, "Can-- can you hit me?"

Sharyn Alfonsi: So you actually put drugs into this person?

Dave Martin: Yeah, I actually -stuck them, drew the blood back. You know, now before when I drew blood back, it would, like, make-- make me sweat 'cause I couldn't wait to hit myself. but this time it was just like god I hope they don't OD and I kill them here you know. But I didn't have any urges or desire or anything, so.

Dr. Rezai's team told us Dave Martin did admit to taking one painkilling pill at a party in December. Still -- 10 of the 15 patients in the ultrasound clinical trials have remained completely drug free.

Dr. Ali Rezai is trying the same ultrasound therapy on 45 more addiction patients and is already thinking about expanding the use of ultrasound to help people with other brain disorders including post traumatic stress disorder and obesity.

Dr. Ali Rezai: This is serious business, research that's never been done before. We have to learn more. We have to replicate our findings.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is there any risk at running towards something quickly?

Dr. Ali Rezai: There's always risk, but you cannot advance and make discoveries without risk. But we need to push forward and take the risk, because people with addiction and Alzheimer's is not going away, it's here so why wait ten, 20 years? Do it now.

Produced by Guy Campanile and Lucy Hatcher. Broadcast associate, Erin DuCharme. Edited by Jorge J. García.

for more features.